Some information about the literary concept behind the 'Seven Ages of Man' album, taken from the Shakespearian play, 'As You Like It'.

In an attempt to codify and understand the human life cycle, artists, writers and scholars throughout history have attempted to split a lifespan into defined and universal ‘ages of man’. Since Greek and Roman antiquity, life has been split into anywhere from three to twelve stages of growth and development. It wasn’t until the Middle Ages that artistic, theological, and scholarly views congregated on the septenary nature of the life cycle. Described as ‘the perfect number’, the number seven had a particular eschatological significance for scholars in the Middle Ages: the seven deadly sins, and the seven things only to be found in the kingdom of heaven (life without death, youth without age…) imbued the number with symmetry and theological significance during that period.

There are frequent artistic representations of and illusions to the ’Seven Ages of Man’ within medieval art and literature. It’s no surprise that this is a concept that both Shakespeare and his audience would have been familiar with, as shown in the rather satirical speech above. Within the speech, Jaques tries to impress upon the listener that selfhood is only performance, with the individual playing different roles in each stage of his life. However, through satire, similes and derision, Jacques is not able to get any closer to articulating what being one’s authentic self ‘outside the stage’ might look like. Arguably, the point Shakespeare is trying to argue is that the method to authentic truth and understanding is not to deride but embrace the attempts of art – to find meaning and understanding of the evolution of an individual human life.

Since then, the concept has inspired a myriad of literary and artistic works, such as the famous series of paintings by Robert Smirke. In identifying the overall structure of a full life, writers and artists hoped to get closer to an understanding of human development and perhaps the purpose of life itself. However, any attempts to classify the ‘ages’ of man, whether in writing, art or indeed music, ultimately reveal more about the author and place of origin than any conclusive truth about the nature of the intangible human spirit.

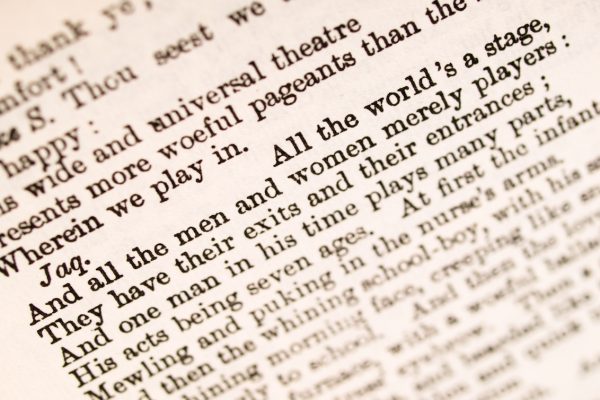

All the world’s a stage

BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

(from As You Like It, spoken by Jaques)

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms;

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lin’d,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion;

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Samuk, Tristan. “Satire and the Aesthetic in As You Like It.” Renaissance Drama, vol. 43, no. 2, 2015, pp. 117–42. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/683106. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

Sears, Elizabeth. The Ages of Man: Medieval Interpretations of the Life Cycle. Princeton University Press, 1986. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvckq7pz. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.